Competing is hard for me. I strive to do everything perfectly. No flaws, no errors, no excuses. This is typical Type-A personality stuff, and everyone knows someone like me. I hate to lose, and I damn sure hate to admit that I lost because of my own efforts (or mistakes). But I also crave feedback. If something I built, wrote, said, designed, grilled, baked, painted, or brewed isn’t quite right, I want to know how to fix it next time around. This is the basic reason why brewing competitions are so awesome.

Who doesn’t want to win? I am a great winner! I am only an okay loser; sometimes I am crushed by not doing great at whatever I attempted. So when I entered my first homebrew competition in 2015 I was pretty excited to get some quality feedback about my beers. I entered three beers and two different wild fermented ciders in hopes of doing well and learning about the process. I was not disappointed, I did both well and utterly terrible at the same time.

The beers I had submitted were:

1) A smoked version of my “BSP” porter (nitro) which I thought would do terrible because it was a nitro version and wouldn’t bottle well. (why no name here, since you offered names for the others?)

2) My “Seastate Schwarzbier,” which I thought would do okay because it was almost indistinguishable from the best commercial example I had ever tried.

3) My “Kings Bay Kolsch,” of which I was the so proud and sure that I fully expected to medal for this beer and put it in the “done column” on our brewery listing of experimental beers.

Before I tell you how I did, I need to explain how a beer is judged. Each beer is submitted under a style profile category—a no-brainer since an Irish Stout and an American IPA are completely different and cannot be compared. Judges are certified by the Beer Judge Certification Program (BCJP) and can be of varying levels of experience, and you have no way of knowing who will judge your beer. Each beer has a theoretical maximum point value of 50. The breakdown of points goes like this:

Aroma (0-12pts), Appearance (0-3pts), Flavor (0-20pts), Mouthfeel (0-5pts) and Overall Impression (0-10pts).

Total score then falls into these categories: A problematic beer (0-13), Fair (14-20), Good (21-29), Very Good (30-37), Excellent (38-44), Outstanding (45-50). (Are the word descriptions here official? Because the scale, to me, seems skewed to favorable descriptions. Seems like the Good should be Fair, the Very Good should be Good, the Excellent should be Very Good, and there should be only one Outstanding/Excellent category)

So how did I do? I logged into the event website to see my scores (the score sheets would arrive several weeks later).Well my porter did about as well as I imagined. I had bottling issues because it was on nitro and I really didn’t know what I was doing, and it was an odd beer with both smoked malt and black strap molasses. I basically got killed in the category,scoring only 24 points. This was bad news, but not unexpected. Had I been able to pour this beer from the tap and hand it to a judge, I think it would have scored a few points higher.

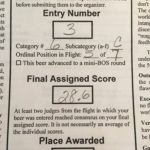

My Kolsch, my pride and joy, scored only slightly higher at 28.6 points (left photo). I was heartbroken when I read the final scores on the event website. Then mad. I worked so hard, perfected my process after two or three batches, and all my friends and family loved it. How could it be so “off” according to the judges? (This is the part where I will remind you that I am only an “okay loser.”)

Several weeks passed before I got my scoresheets in the mail, and when I did, initial anger phase behind me, I took them to heart. This is the best part of competing for me. If you tell me what was out of style or incorrect, I can work on these items, making it better the next time. When you read the comments while looking at the scores, everything can become clearer. That said, beer judging is like watching television or choosing a font for your blog. Everybody has a favorite show or font, and it’s probably not the same as someone else’s favorite. These things are very subjective. Because of the subjectivity of beer tastes, entering the same beer into multiple competitions to be judged by multiple different judges – and palates – can show you a trend in judging and help you make better adjustments. Some of my comments were: “tastes like an okay kolsch, but the color and body are a bit off-style,” “slightly heavy for a kolsch, a bit creamy,” and “generally a good effort but the high astringency detracts from the overall drinkability, watch sparge temperatures/over sparging perhaps, keep at it!”

The comments, and encouragement were just what I needed. I learned a few huge lessons.

1) My individual palate is awful at best. I cannot taste (or smell) at the level necessary to be a judge.

2) My friends are drinking my beer for free, and that alone makes it “better” than it probably is.

3) Kolsch is one of the hardest beers to get right. You are not covering it up with hops, dark malt or adjuncts, so any mistake in recipe, process or fermentation comes right through.

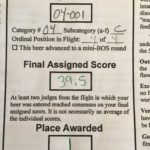

And that leaves the schwarzbier on the beer list (middle photo), so you’ve probably guessed this beer did really well. It finished first in its category (right photo), first for all lagers (1 of 4) and then 10th overall in the Best of Show round. I was completely shocked and very humbled. Once again, the feedback was great and I took it to heart and made a few more tweaks to my recipe in an attempt to make it even better.

So how did my Kolsch do in 2016? Once again, it was crushed. The differences from the kegged version to what was in the bottle were night and day. My feedback from the judges this year was good, and I have a lot of room to improve. So back to the drawing board with hopes of claiming a gold medal next time.

Everyone knows a fresh-picked tomato in late July/August makes the best BLT in the world. An apple pulled off the tree in September/October tastes like nothing else. So why don’t we seek beers like that? We do. The beer world loses its collective mind over some seasonal releases. Take Dogfish Head’s pumpkin beer. Dogfish Head will not brew it without freshly processed pumpkins. Then look at all the “wet hop” or “fresh hop” beers. Brewers have a limited window to get these hops and only hours to brew with them. That’s what makes these beers great.

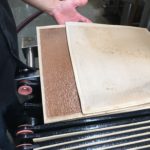

Everyone knows a fresh-picked tomato in late July/August makes the best BLT in the world. An apple pulled off the tree in September/October tastes like nothing else. So why don’t we seek beers like that? We do. The beer world loses its collective mind over some seasonal releases. Take Dogfish Head’s pumpkin beer. Dogfish Head will not brew it without freshly processed pumpkins. Then look at all the “wet hop” or “fresh hop” beers. Brewers have a limited window to get these hops and only hours to brew with them. That’s what makes these beers great.  eer using Gargoyle and Cascade hops. In a 7,000-mile round trip, the Brew Master flew to California, procured the hops, and flew back the same day. Straight from the airport and into the brew kettle. You cannot fake it; you cannot freeze the hops and call it “fresh hopped” beer. You cannot move the date forward for fiscal expediency. You just can’t.

eer using Gargoyle and Cascade hops. In a 7,000-mile round trip, the Brew Master flew to California, procured the hops, and flew back the same day. Straight from the airport and into the brew kettle. You cannot fake it; you cannot freeze the hops and call it “fresh hopped” beer. You cannot move the date forward for fiscal expediency. You just can’t. aroma. It smelled like heaven for almost an hour. Then, raw, unfiltered honey was added for body and to dry out the beer little. Truly, the brewing of this genuinely seasonal beer was amazing, and it will be the first real “honey nut brown” I have had in quite a while. A higher mash temp, a great malt bill and some care will create a truly original, and more importantly, truly SEASONAL beer.

aroma. It smelled like heaven for almost an hour. Then, raw, unfiltered honey was added for body and to dry out the beer little. Truly, the brewing of this genuinely seasonal beer was amazing, and it will be the first real “honey nut brown” I have had in quite a while. A higher mash temp, a great malt bill and some care will create a truly original, and more importantly, truly SEASONAL beer.

At this point in the homebrew infatuation, who hasn’t thought of quitting their day job and going pro? After five or more beers, just about every serious beer drinker (let alone brewer) with whom I’ve ever had a conversation mutters something along the lines of: “Wouldn’t it be effing cool to own your own brewery?” Well, I’ve asked myself, and my adorable wife, that question many, many times.

At this point in the homebrew infatuation, who hasn’t thought of quitting their day job and going pro? After five or more beers, just about every serious beer drinker (let alone brewer) with whom I’ve ever had a conversation mutters something along the lines of: “Wouldn’t it be effing cool to own your own brewery?” Well, I’ve asked myself, and my adorable wife, that question many, many times.

I had another interesting experience with cask conditioned beer on my second trip to Brisbane, Australia. A friend of mine had been there many times, and knew of a place called The Breakfast Creek Hotel (the locals call it the “Brekky Creek”). This place had the best steak house going (the kind where you choose your steak in the case) and the Paddy Fitzgerald Bar, a really cool bar that still serves cask ale. The beer was XXXX Bitter (spoken “four-ex”),made by Castlemain Perkins in Brisbane, Australia. On its own merit, XXXX Bitter is a good beer, a kind of English bitter hybridized with a Czechoslovakian lager yeast. It is great, 4.6% ABV, and crushable. The XXXX Bitter on cask at the Brekky Creek is from another world. There is something amazing that happens in the cask. I don’t know if it is the brewers pitch, the wood, the tradition, or the specter of seeing it tapped with a hammer…but it is amazingly different. I have consumed many, many pints of XXXX Bitter, “off the wood” as the barman says, while at the Brekky Creek and they were all amazing. The cask mellows all the flavors a bit. The bittering from the hops is toned down, and the wood adds a different mouthfeel than you would get from a bottle of standard CO2 draught. The differences to most people would be significant enough to suggest the cask and non-cask versions of the same beer were actually two different beers. As a really cool side note to the Paddy Fitzgerald Bar fame, I would add that they have a very interesting tradition regarding a tapped cask. They finish it that day. Don’t get me wrong, they are small casks (10 gallons/38 liters I believe), but those of you sitting in the bar within an hour of closing could get a special treat. The last time I was there, in 2006, I happened to be there with only four other patrons – two locals and three of us Sailors. The locals kindly accepted the free pitcher that the barman poured for them and took a while to consume it. My friends and I went through pitcher after pitcher of wonderful beer while discussing such lofty topics as US football vs. Rugby, Rugby Union, and Australian Rules. We also debated who had consumed more, and which of us had the largest bladder (Big Head Todd drank way more, and I had the largest bladder).

I had another interesting experience with cask conditioned beer on my second trip to Brisbane, Australia. A friend of mine had been there many times, and knew of a place called The Breakfast Creek Hotel (the locals call it the “Brekky Creek”). This place had the best steak house going (the kind where you choose your steak in the case) and the Paddy Fitzgerald Bar, a really cool bar that still serves cask ale. The beer was XXXX Bitter (spoken “four-ex”),made by Castlemain Perkins in Brisbane, Australia. On its own merit, XXXX Bitter is a good beer, a kind of English bitter hybridized with a Czechoslovakian lager yeast. It is great, 4.6% ABV, and crushable. The XXXX Bitter on cask at the Brekky Creek is from another world. There is something amazing that happens in the cask. I don’t know if it is the brewers pitch, the wood, the tradition, or the specter of seeing it tapped with a hammer…but it is amazingly different. I have consumed many, many pints of XXXX Bitter, “off the wood” as the barman says, while at the Brekky Creek and they were all amazing. The cask mellows all the flavors a bit. The bittering from the hops is toned down, and the wood adds a different mouthfeel than you would get from a bottle of standard CO2 draught. The differences to most people would be significant enough to suggest the cask and non-cask versions of the same beer were actually two different beers. As a really cool side note to the Paddy Fitzgerald Bar fame, I would add that they have a very interesting tradition regarding a tapped cask. They finish it that day. Don’t get me wrong, they are small casks (10 gallons/38 liters I believe), but those of you sitting in the bar within an hour of closing could get a special treat. The last time I was there, in 2006, I happened to be there with only four other patrons – two locals and three of us Sailors. The locals kindly accepted the free pitcher that the barman poured for them and took a while to consume it. My friends and I went through pitcher after pitcher of wonderful beer while discussing such lofty topics as US football vs. Rugby, Rugby Union, and Australian Rules. We also debated who had consumed more, and which of us had the largest bladder (Big Head Todd drank way more, and I had the largest bladder).